The story of ice cream is a 3,000-year journey that begins not with cream, but with snow, fruit, and flowers in ancient Persia. We’ll trace its path from Persian sharbat to Sicilian sorbetto and see how a world war helped crown ice cream the “king” in North America. It’s a history that reveals ice cream’s true ancestor is gelato—and explains why the original often tastes better, and how a few artisans continue to preserve the authentic tradition today.

Here’s what we’ll uncover (click to skip to any section, if you like!):

- Sorbetto(ish) in Ancient Persia: Gelato’s Precursor

- Sorbetto’s Entry into Ancient Rome

- The Renaissance and Birth of Modern Gelato

- Gelato Travels to France (& maybe England): Ice Cream is Born

- Gelato in the New World

- Rise of Popularity: Gelato and Sorbetto in the 21st Century

- Preserving the Tradition of Natural Ingredients and Handcrafted Desserts

- The Future of Gelato: Your Next Scoop

Gelato History Starts Here: “Sorbetto”(ish) in Ancient Persia

Frozen sorbetto-like treats date back to ancient Persia, as far back as 550 BC.

“Sharbat” — sorbetto’s older cousin — is a fruit-based drink originally cooled with mountain snow or ice. Persians used insulated vessels (thinking something like a “zeer” pot, but open to correction!) to carry the snow and ice, then stored it in specially-designed ice houses, or “yakhchal.” Yakhchal made the snow easy to access year-round.

Sharbat not only had a cooling effect, but it was also believed to have medicinal properties. Some recipes used ingredients like saffron or rose water, which were thought to have healing powers.

The Persians also had a particular fondness for sour flavours. Along with flower petals and herbs, sharbat still often includes tart juices like pomegranate, lemon, or sour cherry. To balance the sourness, sugar cane or honey would then be mixed into the drink.

From Persia, sharbat spread throughout the Middle East and then to China and beyond. In fact, legend has it that Alexander the Great was so enamoured with the drink that he brought it home to Greece after his Persian conquest.

Sorbetto’s Entry into Ancient Rome: A Treat for the Senses

Scorched by the heat, citizens of ancient Italy, its citizens loved the icy coolness of sharbat. But how did sharbat arrive in Italy from its Persian birthplace? And how does sharbat become gelato?

Although some believe that ancient Greeks and Romans enjoyed similar frozen desserts, it is widely-accepted that the Arabs introduced frozen fruit juices to Sicily.

This idea claims that Arab conquerors introduced sharbat to Sicily during their 9th-10th century occupation. The Arabs combined Sicilian citrus with sugar and snow to create a local version of sharbat.

Over time, the Sicilians refined the recipe, becoming “sorbetto.”

Curious about the word origin? That’s a mystery, too. Some say it stems from “sharbat”, while others claim it comes from the Latin word “sorbere” (“to sip”).

It’s easy to argue either side, but what we know is that this cool dessert spread like wildfire amongst the Italian elite.

And this leads us to the next question of the evolution: How did sorbetto pave the path for gelato?

The Renaissance and Birth of Modern Gelato: A Treat for the Palate

The 16th century saw the birth of modern gelato, but how sorbetto became gelato is a source of debate. Shrouded in mystery and legend (and doused with Italy’s regional pride, which plays no small part :), let’s present the theories our research churned up:

- Theory 1: As discussed in the last section, there is a common belief that the Arabic invasion of Sicily in the 9th century brought the recipe for sharbat to the island. The next part of the story is that, over time, Sicilian cooks modified their sharbat-turned-sorbetto recipe by adding local ingredients and milk, giving birth to the earliest form of gelato. (Goldstein, Darra. “The Oxford Companion to Sugar and Sweets.” Oxford University Press, 2015)

- Theory 2: Technological advancements in the 1500s drove the transition from sorbetto to gelato. The reintroduction of ice houses, which were popular before the fall of the Roman Empire, made it possible to add milk and eggs to sorbetto. These additions thickened the mixture. (Davis, Joshua and Bruno Tropeano. “Gelato Fiasco: Recipes and Stories from America’s Best Gelato Makers.” Down East Books, 2017)

- Theory 3: Competition between Sicilian gelato makers in the 16th century drove the evolution of sorbetto to gelato. A Sicilian fisherman created the first true gelato by using snow from Mount Etna to make a creamy dessert that he sold from his boat. Other gelato makers followed suit, each trying to outdo the others with their unique flavours and textures. (Clarke, Chris and Richard Hartel. “The Science of Ice Cream.” Royal Society of Chemistry, 2012)

But the two most widely-circulated theories credit two Florentine men, Cosimo Ruggieri (d. 1615; birthdate unknown) and Bernardo Buontalenti (1531-1608).

- Theory 4: Ruggieri served as an alchemist in the court of Catherine de’ Medici. It was for the queen that he created the first-ever gelato flavour, fior di latte (flower of the milk). Legend says that Ruggieri created the creamy dessert as a tribute to the queen, who was known to have a sweet tooth. Fior di Latte is still served today, including at Gina’s Gelato. As it does not contain eggs or cream, it is a logical first attempt at modern-day gelato.

- Theory 5: Bernardo Buontalenti, a Florentine architect, artist, and engineer, is often credited with creating modern-day gelato. He experimented with ingredients and techniques to create a richer, creamier, and more flavourful version: gelato alla crema, the popular egg-cream flavour. Some accounts suggest that Buontalenti’s recipe was circulating as early as 1565. This could predate Ruggieri’s creation.

As cooks experimented with new flavours and techniques, gelato became a luxury symbol.

Where does this delicacy go from Italy?

Gelato Travels to France (& maybe England): Ice Cream is Born

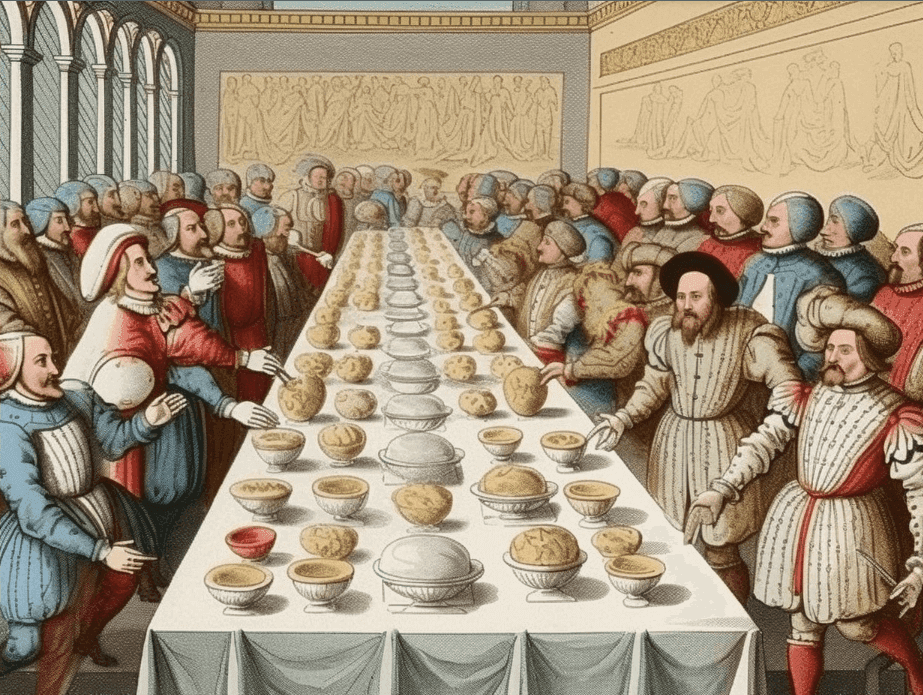

Gelato’s popularity in Italy caught the attention of its northern neighbor, France. In the 1600s, French King Louis XIV enlisted Sicilian chef Francesco Procopio dei Coltelli, renowned for his gelato-making skills, to serve the frozen delicacy to the royal courts.

Procopio’s genius did not stop there. In 1684, he opened Paris’ oldest cafe, Café Procope, to create a haven for the refined gentlemen of Louis XIV’s court. The cafe served as a place for intellectual conversations outside of Paris’ ubiquitous taverns. Revolutionary for its time, Café Procope served coffee instead of wine, which was the norm in Parisian establishments. In fact, Paris’ first taste of coffee, which arrived in Europe from Yemen during the 1670s, was savored here.

But Café Procope’s crowning jewel was gelato. It attracted the city’s elite, including luminaries such as Voltaire and Rousseau. At a time when people obtained ice during cold seasons from lakes and rivers to store in ice boxes for the summer, Procopio’s gelato was a true novelty. His establishment played a pivotal role in popularizing the gelato throughout France.

Over time, the French likely developed their version of gelato by adding eggs and equal parts cream to milk, creating what we now know as ice cream. However, records also show that during the 17th century, a version called “Cream Ice” often appeared on the table of the English king, Charles I. This suggests that either France had a part in influencing its northern neighbour (hard to trace since England, at that time, rarely credited France with anything good ;), or England developed it simultaneously.

Gelato and Sorbetto in the New World: A Treat for the Imagination

While we’re not sure when ice cream first appeared in the Americas (likely the 1700s), the first recorded entry of gelato in North America shows up in 1770 via Giovanni Biasiolo, an Italian immigrant.

The exact details of his arrival and the location of his shop are unclear, but we do know that Biasiolo took out an ad in the Pennsylvania Gazette in 1770. It stated that his concoction was made “…in a particular manner, and is of an extraordinary flavour.”

This ad records the first-known commercial gelato in the Americas. It also predates what is believed to be the first North American ice cream parlour, which opened in New York City in 1790 (“Explore the Delicious History of Ice Cream.” PBS Food: The History Kitchen, Public Broadcasting Service. Accessed April 27, 2023).

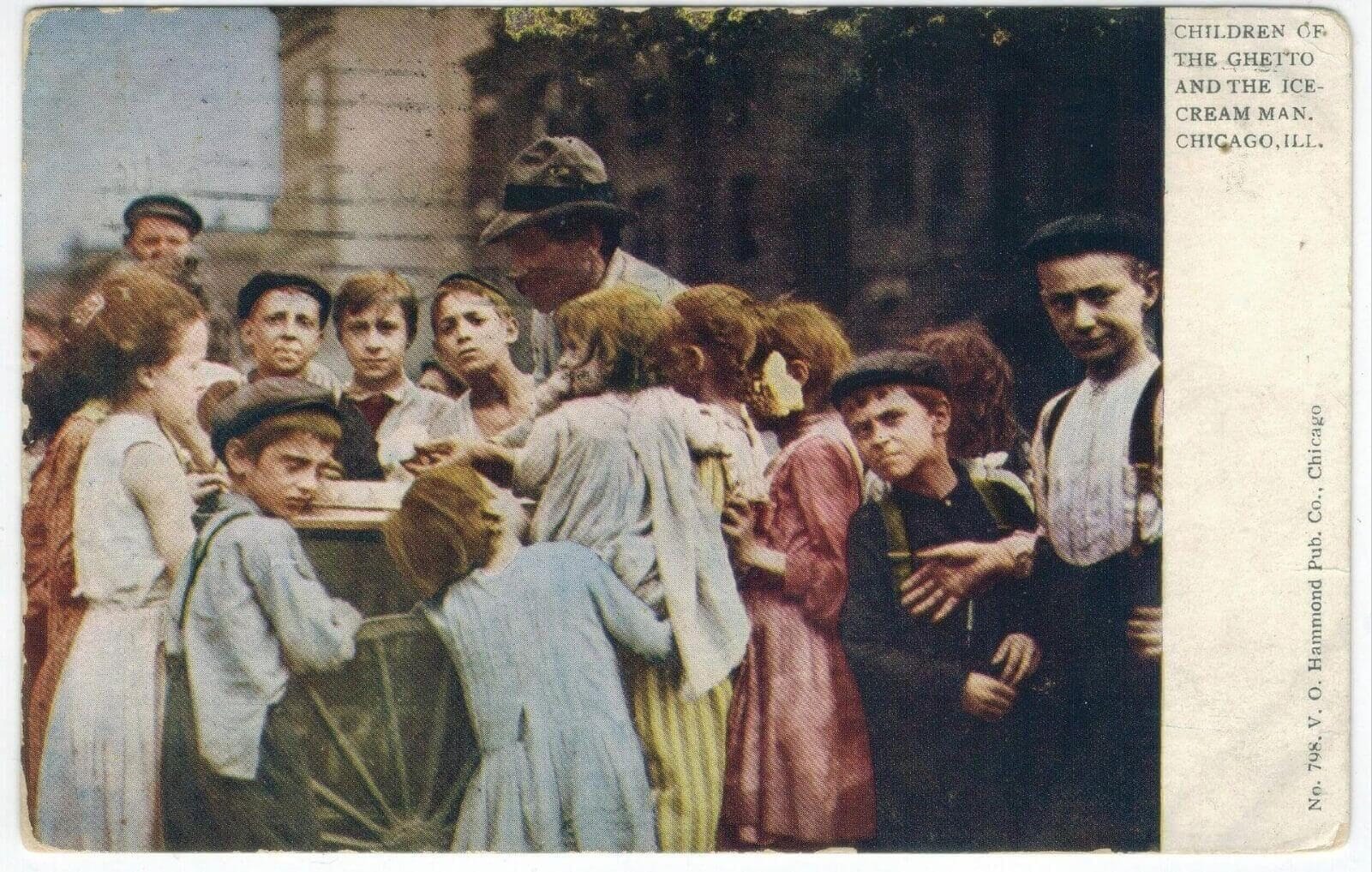

Fast-forward to the late 19th century and gelato started gaining popularity again in the New World. Waves of Italian immigrants crossed the Atlantic and brought with them their gelato-making skills. In the early 20th century, Italian gelato shops began to appear in cities like New York, Chicago, Montreal, and Toronto.

These gelato shops became popular gathering places for Italian communities in North America. Gelato was a symbol of national pride for Italians, served at important events and celebrations.

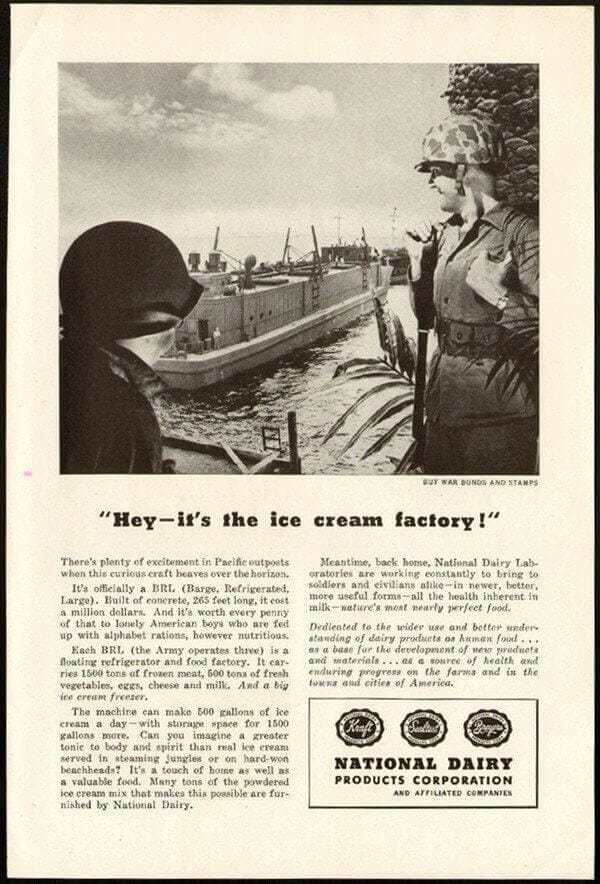

Though they lived side-by-side for years, ice cream needed a boost to become the go-to frozen treat in North America. It came in the form of a world war. There are a couple of reasons why World War II maybe have helped ice cream — and not its older sibling, gelato — take off across North America:

- During WWII, soldiers were regularly given ice cream. According to the International Dairy Foods Association, “Ice cream became an edible morale symbol during World War II. Each branch of the military tried to outdo the others in serving ice cream to its troops. In 1945, the first ‘floating ice cream parlour’ was built for sailors in the western Pacific.” It is likely that returning soldiers continued to crave this frozen treat once they returned from the war.

- In the post-war era, North Americans were enthusiastic about trying the dishes of their allies, such as ice cream from the French and English. They were less willing to try dishes from enemy lines, like gelato from Italy. This sentiment was in part fuelled by wartime propaganda and the desire to distance themselves from the atrocities of the war.

This post-war era gave ice cream the edge it needed to soar past gelato in popularity across North America.

Gelato and Sorbetto for the 21st Century

Rise of Popularity: Gelato and Sorbetto in the 21st Century

Gelato and sorbetto have surged in popularity in the 21st century, and local spins on Italian classics are now offered in gelaterias across North America.

When comparing the two side-by-side, many people prefer traditional gelato over ice cream ice cream. Along with sorbetto, the density, creaminess, and more flavourful quality of true gelato creates a more indulgent treat. With less butterfat and air than ice cream, it also makes gelato healthier (and who wants to eat air?).

(Please excuse our playful jab at ice cream ;).

However, with a rise in popularity comes a rush of people ready to cash in — and this usually means a loss in quality.

By far, the vast majority of current-day ice cream and gelato stores lean on convenience and not craft. Abandoning traditional, from-scratch methods, they favour pre-made bases, syrups, and/or artificial flavours and colours.

These stores reap significant savings in cost and time while the customer experiences a product that’s significantly inferior in taste and health.

However, some artisan shops continue to use traditional recipes and techniques, ensuring that the craft of making gelato and sorbetto is still alive and well.

The Importance of Preserving Traditional Methods

Thankfully, a tiny percentage of today’s gelaterias and ice cream parlours are committed to 100% handmade, from-scratch traditions, using all-natural ingredients.

Seek out these gelaterias (and ice cream parlours). Frequent those that take pride in providing handcrafted indulgence. By honouring the history and cultural significance of this dessert, you’re likely to receive a richly satisfying scoop, and a taste of centuries-old traditions, too.

In these shops, you won’t find brightly-coloured tubs of chemicals posing as treats or gelato that piles sky high into the air. Instead, you’ll be offered authentic — though modest-looking — gelato and ice cream.

While their counterparts may look beautiful with dazzling displays of colours and toppings, don’t judge a book by its cover.

- >Pistachio is not bright green (and neither is mint, for that matter) and doesn’t taste of almonds.

- Pink bubble gum doesn’t exist in nature.

- Real gelato would melt in minutes if piled high in display cases.

Aficionados know that the good stuff lays low and comes toned-down.

Traditional, real-deal gelato and ice cream, free of artificial colours, flavours, stabilizers, and fillers, are a rarity.

They are time-intensive to make.

They often sell out.

And they are a million miles away from the common scoop.

Gina’s Gelato: Preserving the Tradition of Natural Ingredients and Handcrafted Desserts

At Gina’s Gelato, we strive to be among the gelaterias placing priority on handcrafted scoops. Our aim is to deepen appreciation for “slow food” and emphasize traditional, natural ingredients. Whenever possible, we use local ingredients from producers with similar values. We use this approach for everything we serve, from gelato and sorbetto to drinks and desserts.

We take our commitment to handmade seriously. Everything created in our gelateria is handmade, using only natural—and often local—ingredients.

Artificial flavours, stabilizers, fillers, colours, and etc. simply don’t have a place in our kitchen.

We spend time with each element, grinding our almond flour and nut pastes, making apple cider from Kootenay-region apples, rolling our brown-butter cones, cracking eggs from local hens, and pouring dairy from BC cows.

We even go so far as to make our own sweetened condensed milk and bake our own graham crackers when called for in our recipes.

From classic gianduja (we call it “Milk Chocolate Hazelnut”) and stracciatella to unique flavours like Carrot Cake gelato and Bananas Fosters sorbetto, we strive to honour tradition with unique twists.

Our use of natural ingredients and focus on sourcing locally as much as possible creates an experience that honours the rich history of both gelato and our community.

We are working to make our gelateria an experience; one that honours the rich history of gelato and our community.

The Future of Gelato: Your Next Scoop

Next time you indulge in a scoop of a frozen dessert, take a moment to appreciate the centuries of history and innovation that went into creating it. You’re not only enjoying Italy’s rich culinary heritage, you’re tasting a tradition spanning continents and centuries, from a humble frozen dessert in ancient Persia to a treat enjoyed by people across the globe.